Norbert Michel and Jerome Famularo

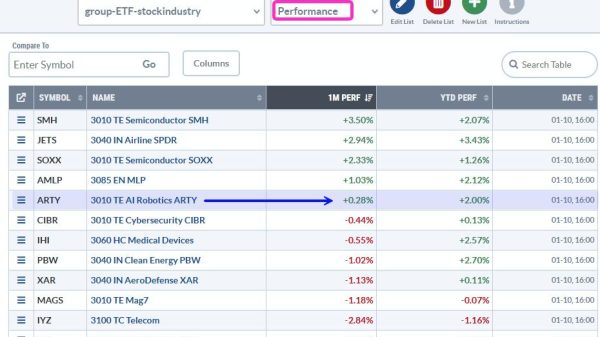

In the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, the United States experienced a much higher rate of inflation than at any time during the prior few decades. Like the prices of many goods and services, the cost of housing rose rapidly, with the median home price increasing almost $100,000. (Figure 1.) Unsurprisingly, many potential homebuyers were—and still are—shocked and upset.

As in years past, many politicians have latched on to the anger surrounding the recent housing market turmoil. During the presidential debate, Vice President Kamala Harris said, “Here’s the thing: we know that we have a shortage of homes and housing. And the cost of housing is too expensive for far too many people.” Prior to the election, Donald Trump outlined his solutions, and now federal officials want to implement a host of policies, ranging from subsidies to selling federal land.

But is the United States really facing a housing crisis? Or a shortage of homes? And should Americans really expect recent federal policy proposals to make housing more affordable?

For the past few weeks, we’ve run a series of posts on Cato at Liberty to examine these questions, and this post is the last in that series. (Previous posts are here, here, here, here, here, and here.) Each post started with the same set of caveats—here’s a shorter version:

- Local officials should relax zoning restrictions and other regulations to make it easier and less costly for people to live, and to allow builders and developers to more easily meet demand.

- Many Americans have taken an economic beating these past few years—real wages have fallen, and prices (including home prices) have not reverted to pre-COVID-19 levels. It is no surprise that so many people have been calling for federal intervention in the hopes of ameliorating that economic burden.

- After staying above 5 percent through early 2023, annual inflation has been below 4 percent since June 2023, and below 3 percent since July 2024. But prices remain well above the pre-pandemic level and many consumers are still upset about high prices.

- Something similar happened in the housing market. The median home price increased by more than $100,000, all the way to $442,600. The fact that it came back down to $415,000 by June 2024 has given little comfort to prospective buyers and made recent buyers uneasy.

It is no surprise that many people have been calling for increased government intervention in the housing market, just as many have been calling for various types of price controls in response to inflation. But there is already a long and problematic history of government intervention in housing markets, most of which has increased housing costs. Based on historical experience, policymakers should reject calls for further intervention and pare back the current level of federal involvement.

There is No Housing “Crisis”—A Recap

Still, there are many good reasons to reject the housing crisis/market failure story. Here are a few of the main reasons, as detailed throughout the series.

- House prices aside and contrary to the conventional wisdom, Americans at all income levels have done increasingly well over the past several decades. For starters, most consumer goods and services have become more affordable over time, and interest rates steadily declined, suggesting that Americans could afford to spend more on housing than they did in the 1960s and 1970s.

- Americans experienced solid income growth over the past five decades. From 1967 to 2023, the share of households earning (in real terms) less than $35,000 fell from 31 percent to 21 percent, and the share earning between $35,000 and $100,000 fell from more than 53 percent to 38 percent. During the same period, the share of households earning more than $100,000 essentially tripled, from 14 percent to 41 percent. Moreover, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the share of Americans making at or below the minimum wage declined from 1.1 percent in 2012 to 0.3 percent in 2022.

- These statistics would be consistent with Americans purchasing bigger homes with more amenities, and that’s exactly what they’ve been doing for decades. They’ve been buying larger houses and living in them with fewer people. Holding both the average home size and household size constant, homes have become slightly more affordable, with the share of household income spent on new homes displaying a slightly decreasing trend since 1975. (We previously addressed this issue when Senator Elizbeth Warren (D‑MA) asked her X followers, “You ever wonder how your grandparents bought a home for seven raspberries, but you can’t afford a one-bedroom apartment?”)

- Work hours needed to afford rent remained stable from 2007 to 2019. Additionally, both rent and food expenditures as a percentage of income varied little until the pandemic. Thus, the recent spike in prices and rents is anomalous—it has certainly been harmful to many people, but it was not indicative of a long-term trend. To the extent that nominal incomes continue to rise, the real effects from this spike will continue to dissipate.

- Even though the US population increased by 130 million people during the past five decades, the homeownership rate remained stable outside of the 2008 crisis. The homeownership rate rose even after prices started spiking in 2019.

- A basic estimate of housing availability shows that housing construction has broadly kept up with population growth. For instance, between 2000 and 2021, the average building units permitted per 100-unit change in population was approximately 93 housing units. This relationship is not necessarily optimal, and more housing could certainly make some people better off, but this relationship makes it extremely difficult to support the idea of a widespread housing shortage or market failure.

- Americans have consistently been choosing to rent and buy in more densely populated areas. These choices reveal that people have a strong preference for living in certain areas—for a variety of reasons—and are willing and able to pay to live in those places. Many people have moved from higher-cost areas to lower-cost areas, but most of these moves were from densely populated areas to other densely populated areas. These patterns tend to contribute to higher nominal house prices partly because new land cannot be produced in the same way that other goods can.

We are not recounting these facts to prove that everyone is just fine, or that more people wouldn’t benefit from lower rents, lower housing prices, or higher income. And we’re certainly not saying that there isn’t excessive federal involvement in mortgage markets, or too much regulation at either the federal or state and local level. We think most people would be doing even better without all the regulation and federal involvement in housing markets. But it’s not true that most Americans are facing some kind of housing crisis.

Throughout this series, we have addressed the main aspects of why America is not in a housing crisis. In the rest of this post, we tie up some loose ends by addressing a few additional arguments offered by proponents of the housing crisis narrative.

Poverty Is the Problem for ELI Households

Interestingly, many groups have implicitly conceded that most Americans can afford housing. They’ve focused, instead, on the plight of the poorest Americans and the absence of certain types of “affordable” housing. For instance, in 2018 the president of the National Low Income Housing Coalition (NLIHC), Diane Yentel, testified that “the shortage of affordable homes is most severe for extremely low-income (ELI) households.” As an example, she offered “a family of four, with two working parents who earn a combined $25,100 annually.” She also testified that “Housing cost burdens make it more difficult for poor households to accumulate emergency savings.”

Yentel is surely correct that high housing costs make it difficult for those in extreme poverty, but so does the cost of everything else. The problem is no more a housing affordability problem than it is any other type of affordability problem. The problem is poverty itself, and that’s a much broader economic issue.

Fortunately, the type of extreme poverty Yentel points to is not pervasive in America.

In 2018, when Yentel testified, the estimated number of all American households with two working parents and two children was 8,287,304. Of those, 144,974 households made less than or equal to $25,100. That’s 1.75 percent of households with two children and two employed parents, and that’s less than 150,000 families in a nation of more than 330 million people. (It’s about 0.1 percent of all American households.) Policymakers should have frank discussions about why those 150,000 families are in poverty, but they should also acknowledge that those families’ situation is far from typical. (That discussion should also include all the federal transfers available to such families, but we’re not getting into that here.)

Addressing the “Starter Home” Debate

The COVID-19 pandemic did little to foster a more focused discussion among policymakers on the plight of extremely impoverished Americans. In her 2023 testimony, Yentel stated that “An underlying cause of America’s housing crisis is the severe shortage of rental homes affordable and available to people with the lowest incomes,” and that this shortage “is a structural feature of the country’s housing system, consistently impacting every state and nearly every community.”

To solve this “crisis,” the NLIHC wants Congress to enact “large-scale, sustained investments and reforms.” Their list of preferred policies includes the expanded use of the federal low-income housing tax credit (LIHTC) to build more “affordable” housing units and expanded funding for the national Housing Trust Fund (to at least $40 billion per year). While the NLIHC is opposed to private investors buying “single-family and multi-family properties” because it increases rents, the group supports legislative efforts to “provide more than $150 billion in critical investments” to help create “nearly 1.4 million affordable and accessible homes.”

The NLIHC and other critics of the US housing market also complain about the disappearance of the “starter home,” one that was small and, supposedly, easily affordable (especially for “young potential homebuyers”). In 2024, the Biden administration released its proposals to address this so-called shortage. The list included a new Neighborhood Homes Tax Credit for “the construction or preservation of over 400,000 starter homes in communities throughout the country,” $1.25 billion for the HOME Investment Partnerships Program (HOME) to “construct and rehabilitate affordable rental housing,” a “First-Generation Down Payment Assistance Program,” and a “one-year tax credit of up to $10,000 to middle-class families who sell their starter home.”

The 2024 Economic Report of the President bemoans that “the fraction of all new single-family homes under 1,400 square feet [starter homes] declined from nearly 40 percent in the early 1970s to about 7 percent in the early 2020s.” (Other critics focus on a lower-than-average price, more in line with home price-to-income ratios from earlier decades, such as $200,000 or $300,000.) We do not dispute this declining share, and our second post presented evidence that the size of newly constructed homes increased for most of the past several decades, though it has fallen slightly since 2015.

We do, however, dispute that the federal government should subsidize the construction of “affordable” homes, whether based on the size or price of “starter homes” in the 1960s or 1970s. Federal officials have no idea what the “right” size home is for any neighborhood (and neither do we), but there is no reason that it should be the same size as it was in the 1960s or 1970s. During those two decades, people were becoming increasingly materially well off, and new houses were getting larger and being shared with fewer people than in the 1950s.

As we’ve detailed in this series, those same trends continued, and people built even larger houses with more amenities than in prior years. Many Americans have chosen to buy those smaller “starter homes” from decades past and replace them with larger, better-equipped ones. But the fact that more people would have been able to afford houses if they had been priced lower—or that every person is unable to pay for the housing that they want—is not a market failure.

In any market, for any given demand, the only way to ensure that everyone can afford the house that they want is to shift the supply curve so far to the right that the market price drops to effectively zero.

We make no judgement as to how low home prices should be and neither should federal officials. It is worth noting, though, that even the “low” price of $200,000—the price that many critics of the disappearing “starter homes” are currently fascinated with—would not really solve the plight of people in extreme poverty.

For instance, for a family such as the one in the NLIHC’s example, earning $25,000 per year, the monthly mortgage payment on a $200,000 house (with zero down payment) would consume almost all the family’s income. The price alone, or even the equivalent cost in rent, says nothing about such a family’s ability to consistently earn higher income. That is, the plight of such Americans is much broader than simply a housing affordability problem.

Another cautionary tale against focusing on the lack of “starter homes” is that the market does adjust to meet demand for smaller homes, even if not to everyone’s satisfaction. The size of newly constructed homes has fallen a bit over the past ten years, and local governments—in places such as Oregon, Texas, and Utah—have started changing their zoning restrictions to allow for the construction of smaller units on lots that were previously reserved for larger homes.

Again, these changes demonstrate that markets are working to provide the kinds of housing that people demand. They’re certainly not indicative of a market failure or a crisis, much less one that requires some kind of massive federal program to build “smaller” or more “affordable” homes. Conducting such an effort—which many groups and politicians are calling for—is just another type of industrial policy that is bound to end as badly as any other industrial policy.

Just as federal officials lack the knowledge to know precisely which consumer goods will be in highest demand in the future, they cannot know which types of housing will be most desired. It is very likely that such a large-scale federal housing program will produce more “starter homes” than people would otherwise want. As with any industrial policy, it is likely that this sort of federal intervention in housing markets will result in “a host of ‘unseen’ costs, such as indirect costs paid by others, deadweight loss for the economy as a whole, opportunity costs, misallocation of resources, unintended consequences, moral hazard and adverse selection, and uncertainty inherent in a system dependent on politics, not the market.”

Conclusion

Our intent for this series has been to demonstrate that claims of a severe shortage or market failure—a housing crisis—in the United States are exaggerated. Long before the recent spike in home prices, many policymakers and groups regularly called for massive federal intervention. They still justify these calls on the grounds that America suffers from a severe shortage of housing. It is an abuse of terms.

Over the past several decades, with a growing population, Americans at all income levels have done increasingly well. Income has grown, most consumer goods and services have become more affordable over time, and fewer people are in poverty. Americans have, for the most part, been purchasing bigger and better-equipped homes, and sharing that space with fewer people. Things could certainly be better, but the notion that the United States suffers from a severe shortage of housing, rising to crisis-level proportions that only massive federal programs can fix, is comical.

Speaking of how things could be better, there’s too much federal intervention in the housing market, and most of it is through the financial system. For instance, through the Federal Housing Administration and Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the federal government makes it easier for millions of people to get home mortgages. This arrangement subsidizes debt, not ownership.

Financial consequences aside, this arrangement brings more buyers into the market, so it increases demand. And because housing supply is always somewhat constrained—it takes time to build, and land cannot be mass-produced to meet demand—the result is upward pressure on prices. In the absence of this kind of federal involvement, it is likely that housing in the United States would be even more affordable. For instance, the slightly decreasing trend (since 1975) in the share of income Americans spend on new homes would likely have decreased more.

Throw in the financial consequences of this debt subsidy arrangement, and paring back federal involvement in housing is a no-brainer.

In closing, we acknowledge that not everyone in America is as materially well off as they could be, that housing markets are not perfect, and that some people would benefit from lower rents and housing prices. But this preference for cheaper housing does not equate to a crisis or market failure, and it does not justify federal intervention. There is already too much government involvement in housing markets. It should be pared back, and the federal government should remain neutral in Americans’ decision to rent or buy. It should do so because it would make markets work better, not because markets have failed.