President Trump signed an executive order on March 20 directing the secretary of education to “take all necessary steps to facilitate the closure of the Department of Education.” My colleague Neal McCluskey has listed the “top five reasons to end the Department of Education.” In this post I’ll expand on Neal’s first point: the department is unconstitutional. And the executive branch has not just the ability but the duty not to enforce unconstitutional laws.

The president takes an oath to “preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States.” As constitutional law scholar Sai Prakash has explained, that oath includes a duty not to enforce statutes that the president has determined in good faith to violate the Constitution. “If the President enforced unconstitutional statutes, he would be a participant in a constitutional violation, rather than acting to defend the Constitution.” That is why Thomas Jefferson refused to enforce the Sedition Act upon taking office as president. As Prakash recounts, Jefferson immediately instructed that all pending prosecution under the Act be dropped because he considered “that act to be no law, because in opposition to the constitution” and therefore resolved to “treat it as a nullity, wherever it comes in the way of my functions.”

Properly understood, this duty requires a president not to enforce unconstitutional statutes or powers even after the Supreme Court has wrongly upheld them. To give one stark example, the Supreme Court wrongly upheld the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II in the Korematsu case. Because internment was grossly unconstitutional, the president had a duty to cease it, and all executive branch officers below the president had a duty not to enforce it. Unfortunately, no one in the executive branch exercised their constitutional duty to stop internment, which led to a prolonged and egregious violation of individual rights.

Some might object that this executive duty usurps the judicial branch’s role as a legal decision-maker. To be sure, if the Supreme Court holds that a statute is unconstitutional, the president has no right to ignore that ruling and enforce the statute anyway just because he disagrees. But it is a very different thing to refuse to enforce a law that the courts have upheld. When it comes to constitutional adjudication, the three branches should serve as three distinct veto gates.

Members of Congress should not vote for unconstitutional laws, the president should not enforce such laws even if they are passed, and the courts should block such laws if they are passed and enforced. Understood this way, only laws that are unanimously understood to be constitutional by all three branches can and should take effect.

We do not yet know which legal arguments the administration will make as it attempts to wind down most of the functions of the Department of Education. The executive order directs that the department should be closed “to the maximum extent appropriate and permitted by law.” That leaves uncertain what particular legal arguments the administration may make. But even if a function of the department is mandated by a statute, the administration would be on firm ground if it argued that the statute itself is incompatible with the Constitution.

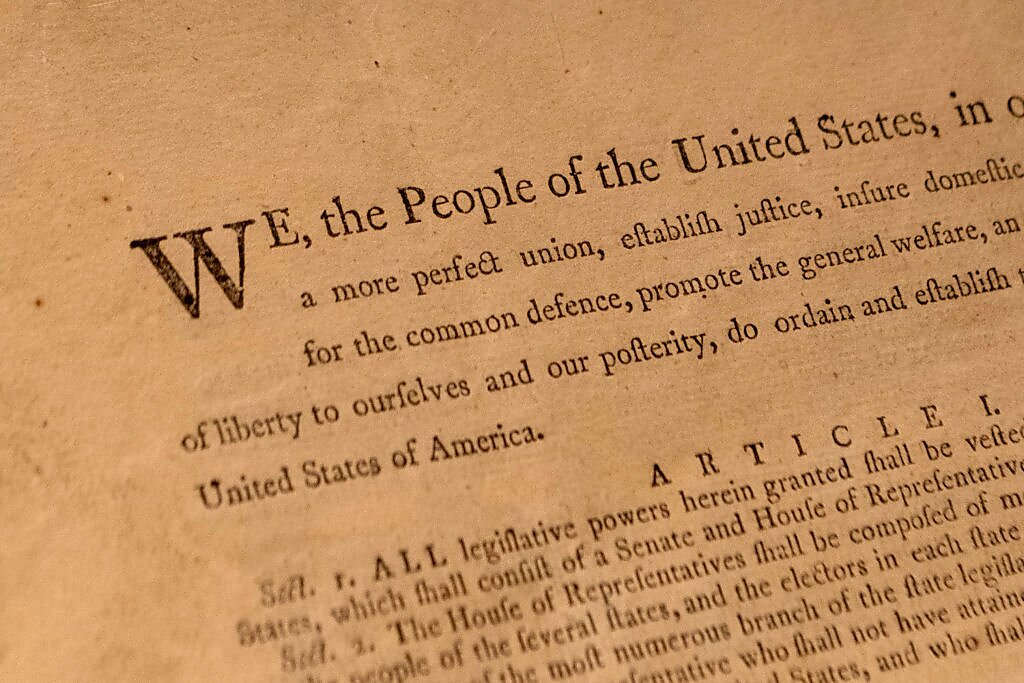

The vast majority of functions carried out by the Department of Education are not authorized by the Constitution. That is because the Constitution grants the federal government only limited, enumerated powers, none of which encompass education policy. Although the federal government may “regulate” interstate commerce, most K‑12 education involves purely intrastate activity. And although money can cross state lines in connection with student loans and other higher education operations, that is not enough to trigger federal jurisdiction. As legal scholar Randy Barnett has shown, the phrase “regulate commerce” had a narrow meaning at the time of the Constitution’s adoption. The federal government’s power was limited to setting uniform rules for trading goods across state lines and ensuring that states did not impede interstate trade.

To be sure, some federal activities related to ensuring educational equality may be authorized under Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment, which allows the federal government to enforce the constitutional guarantee of equal protection. But nearly all other activities of the Education Department are unconstitutional. The president and education secretary should make a clear case for why their oaths to defend the Constitution require this executive action. If they do so, this action could be an important step toward restoring the federal government to its proper role.